Adventurous Kate contains affiliate links. If you make a purchase through these links, I will earn a commission at no extra cost to you. Thanks!

I can pinpoint the moment I became a hip-hop fan. It was October 1994 and I was 10 years old. I was returning from a school field trip to the Bunker Hill Monument, and the boys kept yelling at the bus driver, “One, two, three — NINETY-FOUR POINT FIVE!”

Any Bostonian will immediately recognize that number as Jam’n 94.5 — Boston’s hip-hop station.

The bus driver ignored the boys’ shouts for music. But I didn’t. As soon as I came home, I brought a radio into my room, turned it to 94.5, and felt my world break open. This was my music.

Within weeks I had made my first mix tape, filled with Craig Mack, Shaggy, 2Pac, Naughty by Nature, and the Notorious B.I.G. Soon I was using purple nail polish to paint over the “parental advisory” stickers on my album covers so that my parents wouldn’t notice. I was dancing to Coolio and LL Cool J at middle school dances, and my God, who in their right mind thought “Doin’ It” was a good song to play for sixth-graders?

Looking back, I wonder if my family thought it was a phase. It wasn’t. 24 years later, it’s hip-hop that keeps me awake when driving halfway across Finland. When my friends get pregnant, I ask them if I can play hip-hop when the baby is born. And when I contemplate the pressures I face at the confluence of success, art, and fandom, I turn to the words of Kendrick Lamar.

So when I decided to visit Cleveland, my biggest priority was to explore how hip-hop was represented at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

What is Rock and Roll, Anyway?

A glass I.M. Pei-designed double pyramid on the shores of Lake Erie, the Hall is a celebration of subversion in music. Along with costumes and artifacts from artists across genres — David Bowie’s lightning bolt suit! Michael Jackson’s glove! Flavor Flav’s clock!! — you get a primer on history and influence of music across decades and borders.

Cleveland is an interesting choice for its location. While the city is often a punchline, the little city epitomizing Middle America, I found it to be full of surprises. Full of cultural treasures. Full of interesting people. And quite representative of America as a whole. After all, every four years the nation’s attention pivots to Cuyahoga county, its election turnout often a bellwether of a nation.

So if there were any place to put your finger on the pulse of America, Cleveland is pretty much as close as you can get.

My big concern at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame was whether black artists were given the appropriate credit for the creation of rock and roll. And then I was greeted by one of Biggie’s track suits and a message:

“The more immediate roots of rock and roll lay in the so-called “race” music, or rhythm and blues, and “hillbilly” music, or country & western, of the Forties and Fifties. Other significant influences include blues, jazz, gospel, boogie-woogie, folk and bluegrass…

Over the past five decades, rock and roll has evolved in many directions. Numerous styles of music — from soul to hip-hop, from heavy metal to punk, from progressive rock to electronic — have fallen under the rock and roll umbrella.

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame recognizes these different types of music and looks forward to seeing how rock and roll will continue to reinvent itself in the future.”

–Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

Reading this message truly set a ton for what was to follow — a museum that honored artists in countless genres springing out of rock and roll.

And then there’s the Hall of Fame itself — the list of inductees, which began in 1986. Performers become eligible 25 years after their first single is released, and more than 900 historians, music industry members, and performers vote on the final nominees. In 2012 the Hall added a voting option, and the top five vote-getters from the public receive ballots as well. (Currently Stevie Nicks is in the lead for next year, and if inducted, she would be the first female double inductee.)

The first round of inductees included pioneers like Chuck Berry, Little Richard, and Fats Domino, as well as Ray Charles, Elvis Presley, Sam Cooke, and Buddy Holly. What I love about this list is that it’s so representative of black artists who are so often overlooked in the creation of rock and roll.

As I wandered the Hall, I smiled. I had nothing to worry about. The people who created this museum obviously take music very seriously and want to get it right. The people who complained about hip-hop artists being inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame are nothing but garden-variety internet trolls.

Well. Internet trolls can take various forms.

Hip Hop at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

In 2007, Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five became the first hip-hop artists inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. It was a fitting debut — Grandmaster Flash was among the absolute earliest pioneers of hip-hop in the late 1970s.

Since then, only a handful of hip-hop artists have joined them: Run-DMC in 2009. The Beastie Boys in 2012. Public Enemy in 2013. N.W.A. in 2016. Tupac Shakur in 2017.

And not everyone has been happy about it.

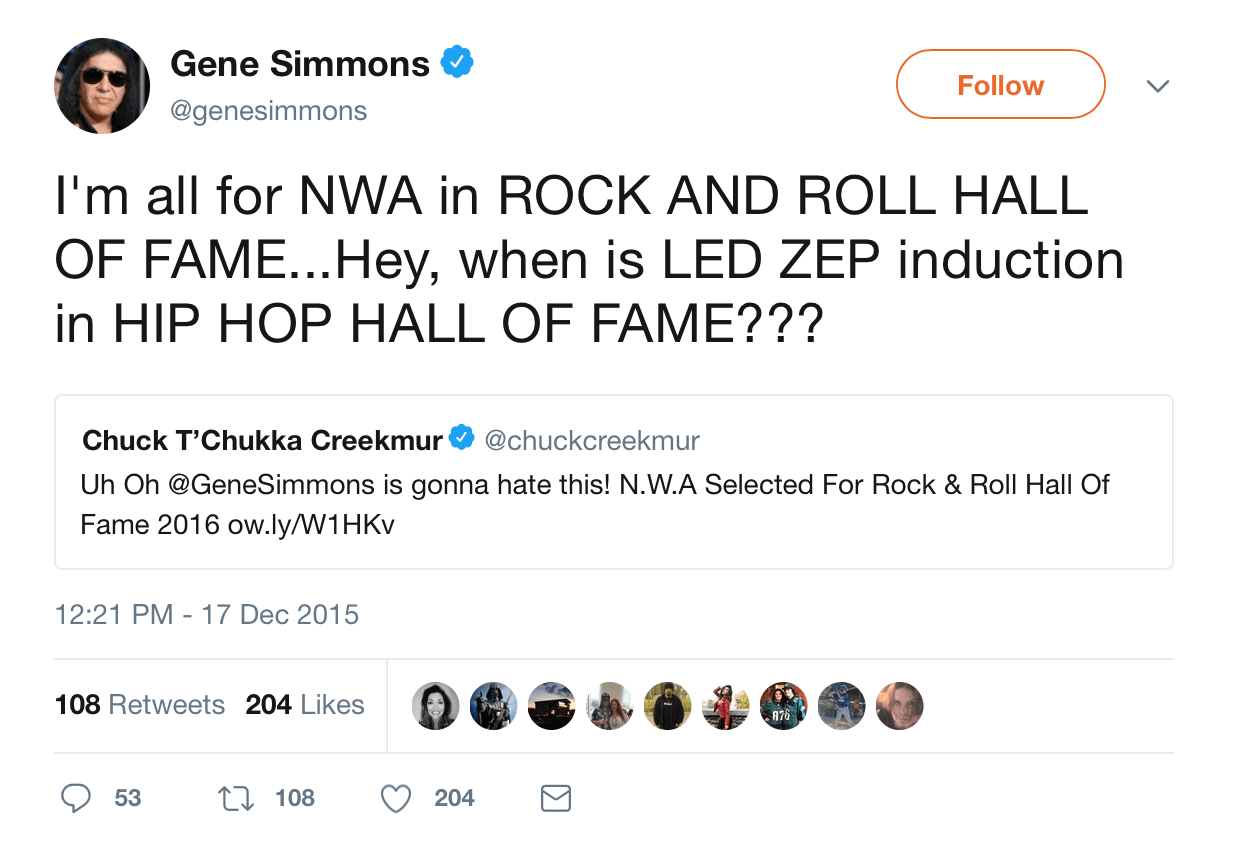

KISS’s Gene Simmons was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2014. That year he told Radio.com, “You’ve got Grandmaster Flash in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame? Run-D.M.C. in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame? You’re killing me. That doesn’t mean those aren’t good artists. But they don’t play guitar. They sample and they talk. Not even sing…If you don’t play guitar and you don’t write your own songs, you don’t belong there.”

This is the same guy who told Rolling Stone, “I am looking forward to the death of rap…Rap will die. Next year, 10 years from now, at some point, and then something else will come along. And all that is good and healthy.”

When you think of internet trolls amplified, think of Gene Simmons. Across America and the world, people like him are repeating that hip-hop and rock are so different — yet if they had actually set foot in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, they would know that wasn’t the case. It’s like saying that baguettes should be excluded from the Museum of Bread, but croissants are totally cool.

Rock and roll was built on a foundation laid by black artists — rhythms that began in Africa and was brought in bondage to the United States. Music that was refined and changed, that branched off into jazz, blues, soul, gospel, and R&B by black artists, and bluegrass, folk, and country by white artists. Music that twisted and turned, found its way back, and grew into something else entirely. Music for which black artists were compensated pennies on the dollars white artists received.

Plenty of people believe rock music started with the Beatles don’t realize that the Beatles’ biggest influence and collaborator was Little Richard. The Beatles sound like the Beatles only because of Little Richard. Think about that.

Yet so many of the white artists who learned from, were influenced by, and appropriated from black artists took all of the money, all of the credit, and all of the success, without giving credit or recognition.

Gene Simmons is the epitome of cultural appropriation in music. He and his bandmates built their success on the influence and inventions of black artists, then he turns to black artists doing the same exact thing as him and says, “You’re doing it wrong and you don’t deserve to be considered rock and roll.”

This exists in subtle ways as well. Compare Usher to Justin Timberlake. Similar age, similar breakout time, similar number of hits, similar blend of R&B and pop, both very talented in singing and dancing. Yet Usher, who was at his critical and commercial peak in 2004 with “Yeah!” and Confessions, never commanded anywhere near the radio play, ticket sales, collaborations, or endorsements of Justin Timberlake.

(Also, would a black artist be given chance after chance to become a leading actor after bombing so embarrassingly and continuously in half a dozen films? “Yeah, but Justin Timberlake’s great on SNL,” you say. Sure — and so is Drake. And Chance the Rapper is better than them both. But I digress.)

Basically, what I’m saying is I want Usher to be able to phone in a mediocre album à la The 20/20 Experience at the last minute and be given the longest performance slot at the Grammy Awards anyway.

Cultural appropriation in music can be hard to understand when so many artists are influenced by each other. It’s more than influence. This is a great resource to understand how it works.

Hip-hop is political, creative, protest music that breaks the rules — and if that’s not the essence of rock and roll, I don’t know what is.

Hip-hop is born out of the struggles of black people — for justice, for equality, for recognition, for money, for love. From Grandmaster Flash’s “The Message” to Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” to 2Pac’s “Changes” to M.I.A.’s “Paper Planes” to Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright,” the best political protest songs of the last 25 years have been in hip-hop. Chuck D once likened hip-hop to “CNN for black people.”

The average rap song is far more political and socially conscious than a song in any other genre today.

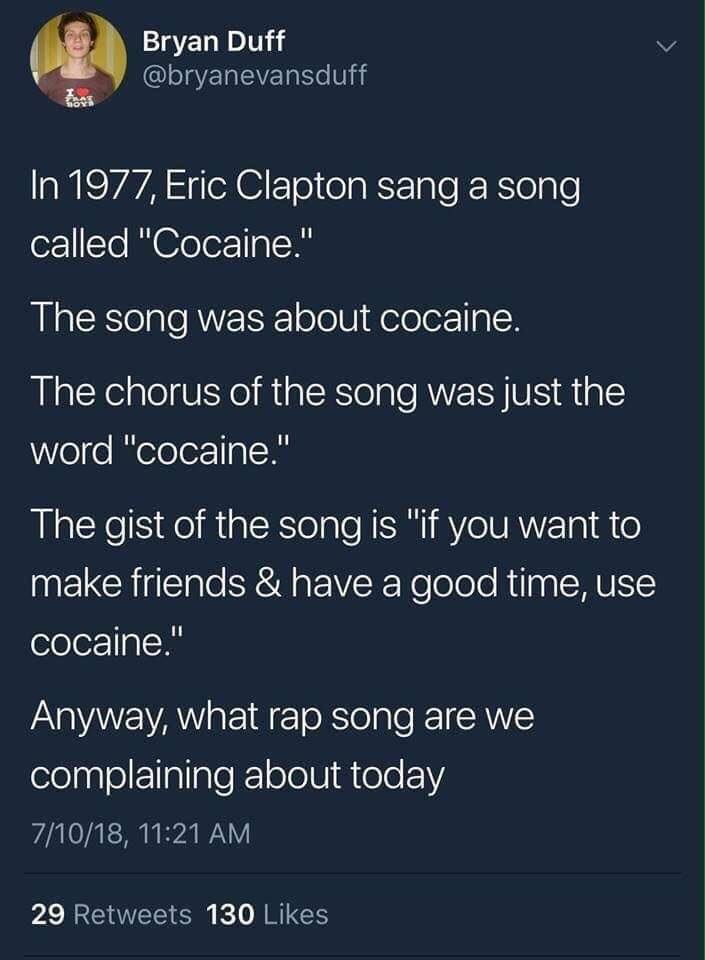

And yet hip-hop is constantly mischaracterized as being “inappropriate” music.

I can give you an example from just a few days ago. In a group chat with my friends, I mentioned that I was rapping Kendrick Lamar’s “Mortal Man” to our friend’s three-month-old baby. (What can I say? That kid loves staring at the ceiling fan and I couldn’t resist bouncing him and singing, When the shit hits the fan, is you still a fan?)

“That’s not appropriate,” one friend said. “You shouldn’t say words like shit to him. I’d rather play my kids Backstreet Boys.”

I responded with three words. “Am I sexual?”

Nearly all pop music is far too mature for children — it just depends on whether it’s overt, subtle, or euphemistic. Just ask my friends who are resorting to playing children’s music, and tearing their hair out at its singsongy repetitions.

(For the record, the baby’s mom is cool with profanity for now. “He’s learning how people make noises. But when he gets older, we’ll cut out the profanity.”)

At the same time, it absolutely infuriates me that an album like To Pimp a Butterfly by Kendrick Lamar — a dense, dizzying intellectual ride and journey through the history of black music alongside black oppression from its beginnings until today, filled with shock and humor, easily the best, smartest, and most important album of the 21st century — can lose the Grammy for Album of the Year to Taylor Fucking Swift.

Because, you know, rap is inappropriate.

Fuck that. That album is smarter than anything else you’ve ever heard.

“Whether hip-hop primarily reflects the culture from which some of it arises — the violence, the despair, the sexism — or gives vent to the frustrations of that culture, remains a question. What is clear is that its main concerns, from simple human relationships to the burning social questions of the day, echo those of early rock and roll.

Hip-hop just pumped up the volume.”

–Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

White artists are allowed to sing about sex, drugs, and crime — yet it’s only hip-hop that gets consistently tainted as being the inappropriate music about drugs and violence and sex. Literally everything is about sex. Everything.

Even when Hamilton came out, the biggest musical of the century so far, I can’t tell you how many people said to me, “Is’t that rap? I don’t like that, I don’t think it’s appropriate.” Come the fuck on.

My hope is that more music fans recognize their prejudices against hip-hop and try, in good faith, to listen to the messages, understand where it’s coming from, and eventually be a fan. I mean, we live in the age of streaming. You can do it for free.

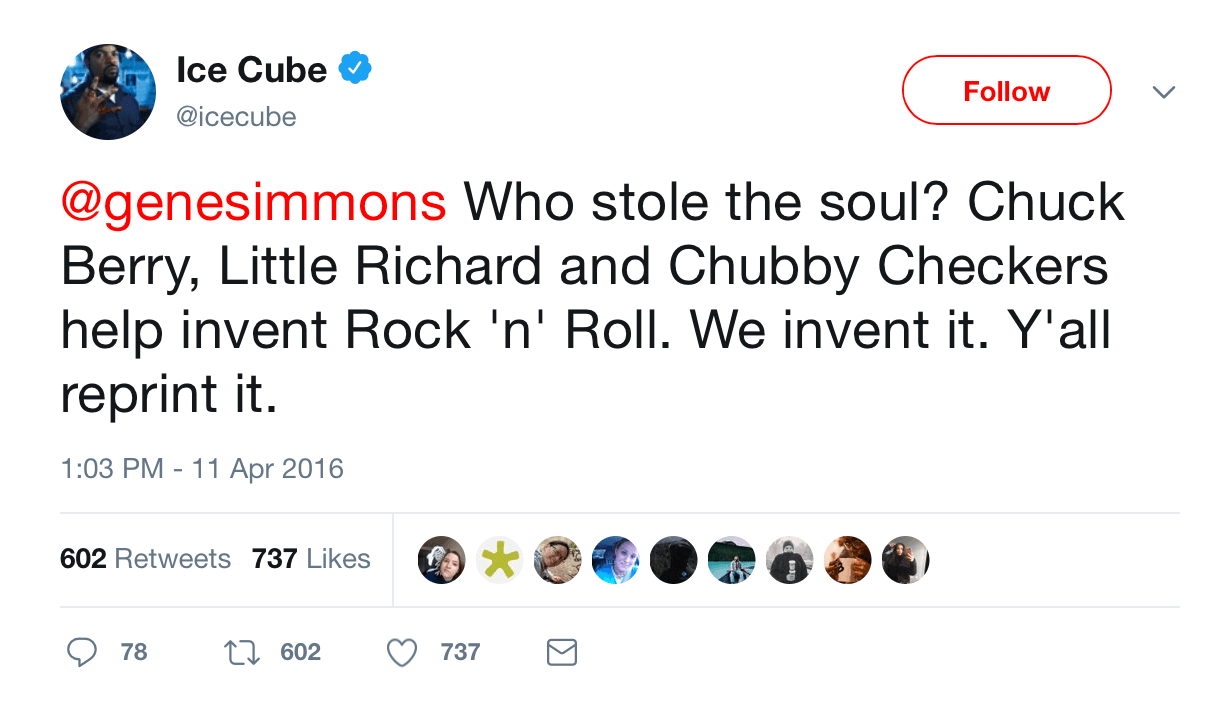

“Now, the question is, are we rock & roll? And I say, you goddamn right we rock & roll. Rock & roll is not an instrument, rock & roll is not even a style of music.

Rock & roll is a spirit. It’s a spirit. It’s been going since the blues, jazz, bebop, soul, R&B, rock & roll, heavy metal, punk rock and yes, hip-hop. And what connects us all is that spirit. That’s what connects us all, that spirit.

Rock & roll is not conforming to the people who came before you, but creating your own path in music and in life. That is rock & roll, and that is us.”

–Ice Cube, at N.W.A.’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction in 2016

Yes. Tupac deserves to be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as much as Pearl Jam.

Run-DMC deserves to be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as much as Metallica.

And N.W.A. deserves to be in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as much as Deep Purple.

What’s next for hip-hop?

Next year, artists who released their first commercial recording in 1993 are eligible for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

That means we might be seeing Outkast on that stage — and I certainly hope we will. Outkast were the first Southern rappers to break through the East-West rivalry and they’re a big part the reason that Atlanta became the hip-hop center of the universe. So many of their songs, from “B.O.B.” to “Ms. Jackson,” defied genre while staying politically conscious — not to mention creating “Hey Ya,” the biggest hit of the early 2000s, and Speakerboxxx/The Love Below, one of only two albums ever to win Album of the Year at the Grammy Awards.

There are plenty more who are eligible as well. A Tribe Called Quest. Wu-Tang Clan. LL Cool J. Snoop Dogg. My top pick? Dr. Dre. While he was inducted as part of N.W.A., he deserves to be recognized on his own, and I fully expect him to be the first hip-hop double inductee.

So perhaps we will see new hip-hop inductees next year. Perhaps we won’t. But if not, well, you better get ready — artists like Jay-Z and Eminem are about to become eligible in the next few years.

“Rock and roll was never written for, or performed for, conservative tastes.”

–Frank Zappa

I come home from Cleveland and stop by my mailbox. Inside are cable bills who ignore my request to go paperless, an Athleta catalogue I didn’t ask for, a check for $69 from the one affiliate company who refuses to join the 21st century — and the latest issue of Vanity Fair. Vanity Fair, arguably the whitest magazine around, with a you-forgot-the-people-of-color scandal nearly every year. I often roll my eyes at the magazine, but it’s some of the best intellectual writing around, and so I subscribe.

On this issue of Vanity Fair, there’s a face I don’t expect to see. A face that brings a smile to mine. And a headline. The Gospel According to Kendrick.

Kendrick, winner of the Pulitzer Prize.

On the cover of Vanity Fair. Only his first name. Not even a “this is a rapper” blurb.

He’s not the first solo rapper to appear on the cover, not the first to be shot by Annie Leibovitz. But this feels…different. He’s not Jay-Z in his tuxedo jacket, talking about his businesses — he’s here as a thought leader, a poet, the intellectual voice of a generation.

I won’t be so audacious as to assume this means things are changing, that black artists will receive the money and credit they deserve, that white artists will eschew appropriation. But there’s something about seeing Kendrick Lamar on the cover, staring straight ahead with clear eyes, that suggests we might be heading in the right direction.

I visited the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a guest of Destination Cleveland, who hosted me in full during my stay in the city. All opinions, as always, are my own.